Good and Evil in Hinduism

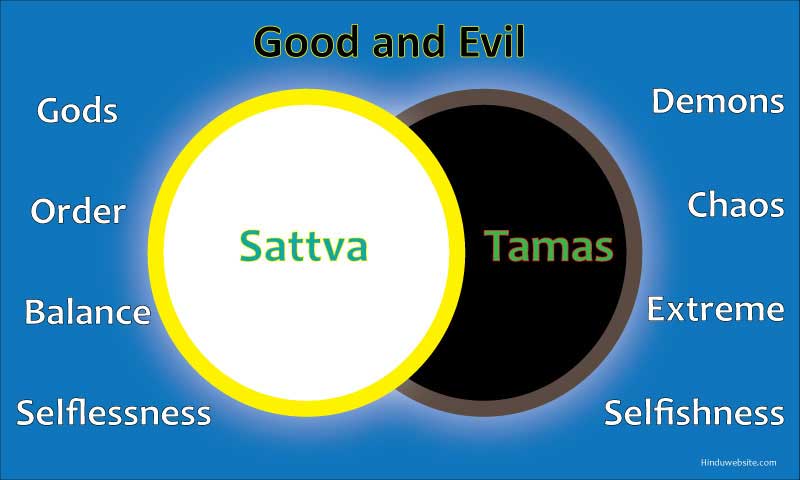

Hinduism clearly identifies the difference between good and evil (dharma and adharma), but their meaning and definition differ from what we traditionally understand. According to Hindu scriptures, good is represented by purity (sattva), light, balance, immortality, order, virtue, and selflessness. Evil is represented by impurity (tamas), darkness, imbalance, extremity, chaos, sinful conduct, and selfishness.

The primary criterion for distinguishing good from evil is intention. In Hinduism, all selfish intentions are evil, and all selfless intentions are good, however trivial they may be. So are the actions and desires which arise from them. If you are selflessly serving others and God, you are on the righteous path (dharma), and if you are selfishly living for yourself and serving your selfish interests, you are on the sinful path (adharma). Good actions lead to meritorious karma (punyam), and evil actions lead to sinful karma (papam).

Meritorious karma (punyam) leads to liberation, peace, and happiness, while sinful karma (papam) leads to suffering, rebirth, a reversal of fortune, and, in extreme cases, an inevitable downfall into the darker and sunless worlds or hells. There is also a grey zone or the middle one, a combination of good and evil, represented by smoke, rebirth, mortality, and suffering, which resembles our existence on earth in many ways.

According to the Hindu Puranas, God stands between order and chaos or, figuratively, between good and evil. Existence is defined by a constant struggle between order and chaos or good and evil. The gods are good, and the demons are evil. Humans stand in between, representing a mixture of both. The dark forces strive hard to disturb the divine order established by the Lord of the Universe (Isvara), while the gods, who represent light and delight, strive to uphold it by doing their part under his watchful gaze.

Humans are often caught between these cosmic battles and become the unwitting witnesses and ultimate sufferers in the play of Isvara. Their lives and destinies depend upon their choices and whether they stand on the side of dharma or adharma. The same struggle goes on in each jiva upon earth, especially humans who possess intelligence and self-awareness. The divinities are also present in our bodies since the human body is modeled on the macrocosm (Viraj). Both are ruled by Death and Time, considered the highest manifestations of Brahman.

Now, what humans are to God, the organs in the body are to humans. They are meant to be used by humans for righteous purposes to uphold dharma. If they are used for selfish purposes, they will accumulate sin and suffer from the consequences. If they are used for selfless services and sacrificial actions, both ritually and spiritually, they accumulate meritorious karma and enjoy the rewards of it. Thus, our lives are shaped by the karma accruing from our good and evil actions. Further, if those actions are performed as an offering to God with a sacrificial attitude, renouncing the desire for their fruit, neither of the karmas accrues, and those who practice it are liberated.

According to the Upanishads, all the organs in the body are susceptible to selfish desires and intentions and, thereby, to evil. Breath (prana) is the only exception. You can see that yourself. Your mind controls the organs in your body. They act according to your good and evil (or selfless and selfish) thoughts or intentions. They follow your will. Your mind can control them and direct them according to your will. However, it is different with your breath. It is not under your control or follows your will, intentions, or the commands from your mind. It remains under the control of your autonomous nervous system. Therefore, whether you desire it or not, will it or not, your breath keeps flowing continuously. Thus, your breath is not vulnerable to evil thoughts or intentions. Evil cannot pierce it.

This is well illustrated in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad in a story in which it was said that once gods and demons had a tussle to control the human body. The gods tried to protect the organs from the demons, but the latter managed to pierce every organ with evil desires and intentions and made them subservient. Thus, under their influence, the eyes, ears, nose, speech, skin, tongue, etc., succumbed to temptations and engaged in desire-ridden actions. Each time the gods tried to protect them, the demons took control of the organs and defeated them. However, when it came to breath (prana) the demons could do nothing. They failed to pierce it with selfish desires and perished. Hence, breath is considered the purifier, preserver, controller, and lord of all the organs in the body. Except for breath (prana), the rest of the organs in the body succumb to selfish desires, while breath remains untouched and untainted. It does not follow our will or intentions. Hence, breath is considered superior to all of them and pranayama (breath control) is used in Yoga to purify the mind and body.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- Hindu Gods - Lord Ganesha

- God and Self in Hinduism

- Goddesses of Hinduism, Their Symbolism and Significance

- Purusharthas in Hinduism

- The History, Antiquity and Chronology of Hinduism

- Ashrama Dharma in Hinduism

- Hinduism and Buddhism

- Death and Afterlife in Hinduism

- Hinduism and Divorce

- Hinduism and Adultery

- Hinduism, Food and Fasting

- The Future of Hinduism

- Good and Evil in Hinduism

- The Hindu Marriage, Past and Present

- What is Maya in Hinduism?

- The Origin and Definition of Hindu

- Hinduism and Polygamy

- Hinduism and polytheism

- Hinduism and Premarital Relationships

- God and Soul, Atma and Paramatma, in Hinduism

- About Suicides in Hinduism

- Religious Tolerance in Hinduism

- Violence and Abuse in Hinduism

- Traditional Status of Women in Hinduism

- Ashtanga Yoga of Patanjali

- About Hanuman or Anjaneya

- Hinduism and Same-sex Marriage

- Perspectives on What Karma Means

- Hinduism - The Role of Shakti in Creation

- Significance of Happiness in Hinduism

- Hindu God Lord Shiva (Siva) - the Destroyer

- The Role of Archakas, Temple Priests, in Hinduism

- Hinduism - Gods and Goddess in the Vedas

- Essays On Dharma

- Esoteric Mystic Hinduism

- Introduction to Hinduism

- Hindu Way of Life

- Essays On Karma

- Hindu Rites and Rituals

- The Origin of The Sanskrit Language

- Symbolism in Hinduism

- Essays on The Upanishads

- Concepts of Hinduism

- Essays on Atman

- Hindu Festivals

- Spiritual Practice

- Right Living

- Yoga of Sorrow

- Happiness

- Mental Health

- Concepts of Buddhism

- General Essays