Hindu Manners, Customs And Ceremonies

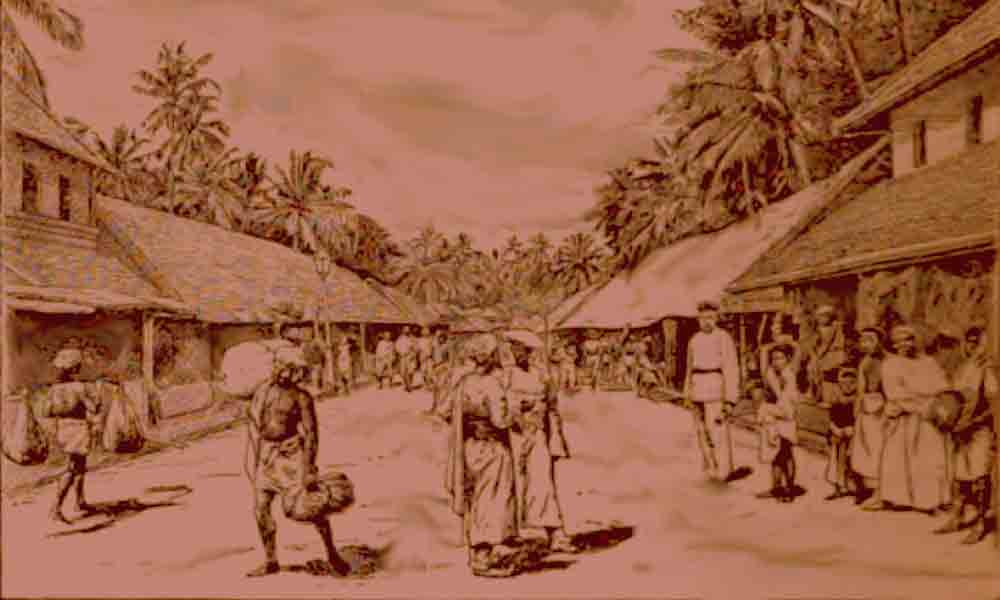

Bazaar in Trivendrum, Kerala, in British Times

Introduction

The following is a reproduction of the first five chapters of the book entitled Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies by Abbe J.A. Dubois. They deal with the caste system and the social conditions prevailing in India nearly 200 years ago. The book was originally written in French during the author's stay in the British India between 1792 and 1823. It was subsequently translated into English by Henry K. Beauchamp and published in 1906. Abbe Dubois' work is a sincere but somewhat prejudiced and misconstrued documentation of the conditions prevailing in India during his stay in the country as a Christian Missionary. As he himself admitted, the main motivation for his work was his belief that "a faithful picture of the wickedness and incongruities of polytheism and idolatry would by its very ugliness help greatly to set off the beauties and perfections of Christianity."

We do not know how far he succeeded in his mission to contrast the so called "ugliness" of Hinduism with his dogmatic notions of Christianity. However, during the course of his work and probably his stay in the country, Abbe Duboi tried his best, though he did not seem to succeed fully, to look at Hindu society with the eyes of an educated and well informed native. Evidently, he was hopeful of the emergence of Christianity as the future religion of the Indians, but took care not to show his prejudices while discussing some historical and traditional aspects of Hinduism. In the first part of the book he presented comprehensive information on the Hindu caste system with particular emphasis on the the castes that lived on the fringes of Hindu society and which could be targeted for missionary activity. While doing so he could hardly suppress his disgust against some castes and communities for their beliefs, rituals and life styles.

We cannot say that his work truly represents the conditions prevailing in India during his stay. Undoubtedly it contains many half truths and sweeping statements. All the same, it carries some historical value and offers valuable insights for people interested in knowing the conditions prevailing in southern India, in the early 19th century. The author is well aware of the diversity of Indian society and the difficulties involved in documenting it accurately, which he himself admitted. In order to maintain objectivity, he said to have adopted the life style of Hindus, including their way of dressing. The book is not without exaggerations and errors of judgment. But from a historical perspective, it deserves a careful study.

Jayaram V

Hinduwebsite.com

Contents

|| Chapter 1 || Chapter 2 || Chapter 3 || Chapter 4 || Chapter 5 ||

GENERAL VIEW OF SOCIETY IN INDIA, AND GENERAL REMARKS ON THE CASTE SYSTEM

CHAPTER I

Division and Subdivision of Castes. — Castes peculiar to Certain Pro- vinces. — Particular Usages of some Castes. — Division of Castes founded on Parentage. — Subordination of Castes. — Outward Signs of certain Castes. — Division of Caste-groups into Right-hand and Left-hand.

The word caste is derived from the Portuguese, and is used in Europe to designate the different tribes or classes into which the people of India are divided 1. The most ordinary classification, and at the same time the most ancient, divides them into four main castes. The first and most distinguished of all is that of Brahmana, or Brahmins ; the second in rank is that of Kshatriyas, or Rajahs ; the third the Vaisyas, or Landholders and Mer- chants ; and the fourth the Sudras, or Cultivators and Menials.

The functions proper to each of these four main castes are : for Brahmins, priesthood and its various duties ; for Kshatriyas, military service in all its branches ; for Vaisyas, agriculture, trade, and cattle-breeding ; and for Sudras, general servitude. But I will describe more fully hereafter the several social distinctions which are attached to each of them.

1 The Sanskrit word is Varna = colour, thus showing that upon the difference of colour between the Aryan Brahmins and the aboriginal inhabitants the distinction of caste was originally founded. — Pope.

THE FOUR MAIN CASTES

Each of the four main castes is subdivided into many others, the number of which it is difficult to determine because the subdivisions vary according to locality, and a sub-caste existing in one province is not necessarily found in another.

Amongst the Brahmins of the south of the Peninsula, for example, there are to be found three or four principal divisions, and each of these again is subdivided into at least twenty others. The lines of demarcation between them are so well defined as to prevent any kind of union between one sub-caste and another, especially in the case of marriage.

The Kshatriyas and Vaisyas are also split up into many divisions and subdivisions. In Southern India neither Kshatriyas nor Vaisyas are very numerous ; but there are considerable numbers of the former in Northern India. Howbeit, the Brahmins assert that the true Kshatriya caste no longer exists, and that those who pass for such are in reality a debased race.

The Sudra caste is divided into most sub-castes. Nobody in any of the provinces where I have lived has ever been able to inform me as to the exact number and names of them. It is a common saying, however, that there are 18 chief sub-castes, which are again split up into 108 lesser divisions.

The Sudras are the most numerous of the four main castes. They form, in fact, the mass of the population, and added to the Pariahs, or Outcastes, they represent at least nine-tenths of the inhabitants. When we consider that the Sudras possess almost a monopoly of the various forms of artisan employment and manual labour, and that in India no person can exercise two professions at a time, it is not surprising that the numerous individuals who form this main caste are distributed over so many distinct branches.

However, there are several classes of Sudras that exist only in certain provinces. Of all the provinces that I lived in, the Dravidian, or Tamil, country is the one where the ramifications of caste appeared to me most numerous. There are not nearly so many ramifications of caste in Mysore or the Deccan. Nowhere in these latter provinces have I come across castes corresponding to those which are known in the Tamil country under the names of MoodeUy, Agambady, Nattaman, Totiyar, Udaiyan, VcUeyen, Upiliyen, Pollen, and several others 1 .

CASTES PECULIAR TO CERTAIN PROVINCES

It should be remarked, however, that those Sudra castes which are occupied exclusively in employments indispens- able to all civilized societies are to be found everywhere under names varying with the languages of different localities. Of such I may cite, amongst others, the gar- deners, the shepherds, the weavers, the Panchalas (the five castes of artisans, comprising the carpenters, gold- smiths, blacksmiths, founders, and in general all workers in metals), the manufacturers and venders of oil, the fishermen, the potters, the washermen, the barbers, and some others. All these form part of the great main caste of Sudras ; but the different castes of cultivators hold the first rank and disdainfully regard as their inferiors all those belonging to the professions just mentioned, refusing to eat with those who practise them.

In some districts there are castes which are not to be met with elsewhere, and which may be distinguished by peculiarities of their own. I am not aware, for example, that the very remarkable caste of Nairs, whose women enjoy the privilege of possessing several husbands, is to be found anywhere but in Travancore 2 . Amongst these same people, again, is another distinct caste called Nambudiri, which observes one abominable and revolting custom. The girls of this caste are usually married before the age of puberty ; but if a girl who has arrived at an age when the signs of puberty are apparent happens to die before having had intercourse with a man, caste custom rigorously demands that the inanimate corpse of the deceased shall be subjected to a monstrous connexion. For this purpose the girl's parents are obliged to procure by a present of money some wretched fellow willing to consummate such a disgusting form of marriage : for were the marriage not consummated the family would consider itself dishonoured.

1 Moodelly, ' chief man ' or highly respectable trader. Agambady, he who performs menial offices in temples or palaces. Nattaman, a caste of cultivators. Totiyar, a caste of labourers. Udaiyan, a potter. Yaleyen, a fisherman. Upiliyen, salt manufacturer. Fallen, agriculturist. — Ed.

2 It would be more correct to say West Coast. Moreover, although Xair women are commonly described as polyandrous, they are not really so, for though they enjoy the privilege of changing their husbands, they do not entertain more than one husband at a time. — Ed.

CASTES PECULIAR TO CERTAIN PROVINCES

The caste of Kullars, or robbers, who exercise their calling as an hereditary right, is found only in the Marava country, which borders on the coast, or fishing, districts. The rulers of the country are of the same caste. They regard a robber's occupation as discreditable neither to themselves nor to their fellow castemen, for the simple reason that they consider robbery a duty and a right sanctioned by descent. They are not ashamed of their caste or occupation, and if one were to ask of a Kullar to what people he belonged he would coolly answer, ' I am a robber ! ' This caste is looked upon in the district of Madura, where it is widely diffused, as one of the most distinguished among the Sudras.

There exists in the same part of the country another caste, known as the Totiyars, in which brothers, uncles, nephews, and other near relations are all entitled to possess their wives in common.

In Eastern Mysore there is a caste called Morsa-Okkala- Makkalu, in which, when the mother of a family gives her eldest daughter in marriage, she is obliged to submit to the amputation of two joints of the middle finger and of the ring finger of the right hand. And if the bride's mother be dead, the bridegroom's mother, or in default of her the mother of the nearest relative, must submit to this eruel mutilation 1 .

1 Whatever may have been the case in the days of the Abbe, these customs no longer exist. In regard to this, Mr. W. Logan, in his Manual of Malabar, writes thus : ' To make tardy retribution — if it deserves such a name — to women who die unmarried, the corpse, it is said, cannot be burnt till a tali string (the Hindu equivalent of the wedding- ring of Europe) is tied round the neck of the corpse, while lying on the funeral pile, by a competent relative. Nambudiris are exceedingly reticent in regard to their funeral ceremonies and observances, and the Abbe Dubois' account of what was related to him regarding other observances at this strange funeral-pile marriage requires confirmation.' Careful inquiries made of the leading members of the Nambudiri com- munity and of others in Malabar who have an intimate knowledge of Nambudiri customs have convinced me that the Abbe must have mis- understood his informant in regard to the practice which he records here. What is done in such a case is merely to perform the religious rites, usually associated with Hindu marriages, over the dead body of the woman before the corpse is cremated. By marriage here is meant merely the tying of the tali (the emblem of marriage) and not the act of consummation of marriage. — Ed.

SPECIAL CASTE CUSTOMS

Many other castes exist in various districts which are distinguished by practices no less foolish than those above mentioned.

Generally speaking, there are few castes which are not distinguished by some special custom quite apart from the peculiar religious usages and ceremonies which the com- munity may prescribe to guarantee or sanction civil con- tracts. In the cut and colour of their clothes and in the style of wearing them, in the peculiar shape of their jewels and in the manner in which they are displayed on various parts of the person, the various castes have many rules, each possessing its own significance. Some observe rites of their own in their funeral and marriage ceremonies : others possess ornaments which they alone may use, or flags of certain colours, for various ceremonies, which no other caste may carry. Yet, absurd as some of these practices may appear, they arouse neither contempt nor dislike in members of other castes which do not admit them. The most perfect toleration is the rule in such matters. As long as a caste conforms on the whole to the recognized rules of decorum it is permitted to follow its own bent in its domestic affairs without interruption, and no other castes ever think of blaming or even criticizing it, although its practices may be in direct opposition to their own.

There are, nevertheless, some customs which, although scrupulously observed in the countries where they exist, are so strongly opposed to the rules of decency and decorum generally laid down that they are spoken of with dis- approbation and sometimes with horror by the rest of the community. The following may be mentioned among practices of this nature.

In the interior of Mysore, women are obliged to accom- pany the male inmates of the house whenever the latter retire for the calls of nature, and to cleanse them with water afterwards. This practice, which is naturally viewed

1 This custom is no longer observed ; instead of the two ringers being amputated, they are now merely bound together and thus rendered unfit for use. — Ed.

USE OF INTOXICATING LIQUORS

with disgust in other parts of the country, is here regarded as a sign of good breeding and is most carefully observed 1 .

The use of intoxicating liquors, which is condemned by respectable people throughout almost the whole of India, is nevertheless permitted amongst the people who dwell in the jungles and hill tracts of the West Coast. There the leading castes of Sudras, not excepting even the women and children, openly drink arrack, the brandy of the country, and toddy, the fermented juice of the palm. Each inhabitant in those parts has his toddy-dealer, who regularly brings him a daily supply and takes in return an equivalent in grain at harvest time.

The Brahmin inhabitants of these parts are forbidden a like indulgence under the penalty of exclusion from caste. But they supply the defect by opium, the use of which, although universally interdicted elsewhere, is never- theless considered much less objectionable than the use of intoxicating liquors.

The people of these damp and unhealthy districts have no doubt learnt by experience that a moderate use of spirits or opium is necessary for the preservation of health, and that it protects them, partially at any rate, against the ill effects of the malarious miasma amidst which they are obliged to live. Nothing indeed but absolute necessity could have induced them to contravene in this way one of the most venerable precepts of Hindu civilization.

The various classes of Sudras who dwell in the hills of the Carnatic observe amongst their domestic regulations a practice as peculiar as it is disgusting. Both men and women pass their lives in a state of uncleanness and never wash their clothes. When once they have put on cloths fresh from the looms of the weavers they do not leave them off until the material actually drops from rottenness. One can imagine the filthy condition of these cloths after they have been worn day and night for several months soaked with perspiration and soiled with dirt, especially in the case of the women, who continually use them for wiping their hands, and who never change their garments until wear and tear have rendered them absolutely useless.

1 If this custom ever existed, the spread of education has effectually put a stop to it. — Ed.

A SABBATH OF THE 'LINGAYATS'

Yet this revolting habit is most religiously observed, and, if anybody were so rash as to wash but once in water the cloths with which he or she is covered, exclusion from caste would be the inevitable consequence. This custom, however, may be due to the scarcity of water, for in this part of the country there are only a few stagnant ponds, which would very soon be contaminated if all the in- habitants of a village were allowed to wash their garments in them.

Many religious customs are followed only by certain sects, and are of purely local character. For instance, it is only in the districts of Western Mysore that I have observed Monday in each week kept nearly in the same way as Sunday is among Christians. On that day the villagers abstain from ordinary labour, and particularly from such as, like ploughing, requires the use of oxen and kine. Monday is consecrated to Basava (the Bull), and is set apart for the special worship of that deity. Hence it is a day of rest for their cattle rather than for themselves.

This practice, however, is not in vogue except in the districts where the Lingayats, or followers of Siva 1 , pre- dominate. This sect pays more particular homage to the Bull than the rest of the Hindus ; and, in the districts where it predominates, not only keeps up the strict observ- ance of the day thus consecrated to the divinity, but forces other castes to follow its example.

Independently of the divisions and subdivisions common to all castes, one may further observe in each caste close family alliances cemented by intermarriage. Hindus of good family avoid as far as possible intermarriage with families outside their own circle. They always aim at marrying their children into the families which are already

1 Mr. L. Rice, in his Mysore and Coorg, remarks : ' Lingayats : The distinctive mark of this caste is the wearing on the person of a Jangama lingam, or portable linga. It is a small black stone about the size of an acorn, and is enshrined in a silver box of peculiar shape, which is worn suspended from the neck or tied round the arm. The followers of Basava (the founder of the sect, whose name literally means Bull, was in fact regarded as the incarnation of Nandi, the bull of Siva) are properly called Liugavantas, but Lingayats has become a well-known designation, though not used by themselves, the name Sivabhakta or Sivachar being one they generally assume.' — Ed.

CLOSE MARRIAGE RELATIONSHIPS 21

allied to them, and the nearer the relationship the more easily are marriages contracted. A widower is remarried to his deceased wife's sister, an uncle marries his niece, and a first cousin his first cousin. Persons so related possess an exclusive privilege of intermarrying, upon the ground of such relationship ; and, if they choose, they can prevent any other union and enforce their own pre- ferential right, however old, unsuited, infirm, and poor they may be 1 .

In this connexion, however, several strange and ridiculous distinctions are made. An uncle may marry the daughter of his sister, but in no case may he marry the daughter of his brother. A brother's children may marry a sister's children, but the children of two brothers or of two sisters may not intermarry. Among descendants from the same stock the male line always has the right of contracting marriage with the female line ; but the children of the same line may never intermarry.

The reason given for this custom is that children of the male line, as also those of the female line, continue from generation to generation to call themselves brothers and sisters for as long a time as it is publicly recognized that they spring from the same stock. A man would be marry- ing his sister, it would be said, if the children of either the male or the female line intermarried amongst themselves ; whereas the children of the male line do not call the children of the female line brothers and sisters, and vice versa, but call each other by special names expressive of the relation- ship. Thus a man can, and even must, marry the daughter of his sister, but never the daughter of his brother. A male first cousin marries a female first cousin, the daughter of his maternal aunt ; but in no case may he marry the daughter of his paternal uncle.

This rule is universally and invariably observed by all castes, from the Brahmin to the Pariah. It is obligatory on the male line to unite itself with the female line. Agree- ably to this a custom has arisen which so far as I know is peculiar to the Brahmins. They are all supposed to know the gotram or stock from which they spring : that is to say, they know who was the ancient Muni or devotee from whom they descend, and they always take care, in order to avoid intermarriage with a female descendant of this remote priestly ancestor, to marry into a gotram other than their own.

1 This custom is gradually giving way now amongst the higher castes. —Ed.

VAISYAS AND SUDRAS

Hindus who cannot contract a suitable marriage amongst their own relations are nevertheless bound to marry in their own caste, and even in that subdivision of it to which they belong. In no case are they permitted to contract marriages with strangers. Furthermore, persons belonging to a caste in one part of the country cannot contract marriages with persons of the same caste in another part, even though they may be precisely the same castes under different names. Thus the Tamil Yedeyers and the Canarese Uppareru would never consent to take wives from the Telugu Gollavaru and the Tamil Pillay, although the first two are, except for their names, identical with the second two.

The most distinguished of the four main castes into which the Hindus were originally separated by their first legislators is, as we have before remarked, that of the Brahmins. After them come the Kshatriyas, or Rajahs. Superiority of rank is at present warmly contested between the Vaisyas, or merchants, and the Sudras, or cultivators. The former appear to have almost entirely lost their superiority except in the Hindu books, where they are invariably placed before the Sudras. In ordinary life the latter hold themselves to be superior to the Vaisyas, and consider themselves privileged to mark their superiority in many respects by treating them with contumely.

With regard to the Vaisya caste an almost incredible but nevertheless well-attested peculiarity is everywhere observable. There is not a pretty woman to be found in the caste. I have never had much to do with the women of the Vaisya caste ; I cannot therefore without injustice venture to add my testimony to that of others on this subject ; but I confess that the few Vaisya women I have seen from time to time were not such as to afford me an ocular refutation of the popular prejudice. However, Vaisya women are generally wealthy, and they manage to make up for their lack of beauty by their elegant attire.

SUB-DIVISIONS OF CASTES

Even the Brahmins do not hold the highest social rank undisputed. The Panchalas, or five classes of artisans already mentioned, refuse, in some districts, to acknow- ledge Brahmin predominance, although these five classes themselves are considered to be of very low rank amongst the Sudras and are everywhere held in contempt. Brahmin predominance is also still more warmly contested by the Jains, of whom I have treated in one of the Appendices to this work.

As to the particular subdivisions of each caste it is difficult to decide the order of hierarchy observed amongst them. Sub-castes which are despised in one district are often greatly esteemed in another, according as they con- duct themselves with greater propriety or follow more important callings. Thus the caste to which the ruler of a country belongs, however low it may be considered elsewhere, ranks amongst the highest in the ruler's own dominions, and every member of it derives some reflection of dignity from its chief.

After all, public opinion is the surest guide of caste superiority amongst the Sudras, and a very slight acquain- tance with the customs of a province and with the private life of its inhabitants will suffice for fixing the position which each caste has acquired by common consent.

In general it will be found that those castes are most honoured who are particular in keeping themselves pure by constant bathing and by abstaining from animal food, who are exact in the observance of marriage regula- tions, who keep their women shut up and punish them severely when they err, and who resolutely maintain the customs and privileges of their order.

Of all the Hindus the Brahmins strive most to keep up appearances of outward and inward purity by frequent ablutions and severe abstinence not only from meat and everything that has contained the principle of life, but also from several natural products of the earth which prejudice and superstition teach them to be impure and defiling. It is chiefly to the scrupulous observance of such customs that the Brahmins owe the predominance of their illustrious order, and the reverence and respect with which they are everywhere treated.

RIGHHT-HAND AND LEFT-HAND FACTIONS

Amongst the different classes of Sudras, those who permit widow remarriage are considered the most abject, and. except the Pariahs, I know very few castes in which such marriages are allowed to take place openly and with the sanction of the caste l .

The division into castes is the paramount distinction amongst the Hindus ; but there is still another division, that of sects. The two best known are those of Siva and Vishnu, which are again divided into a large number of others.

There are several castes, too, which may be distinguished by certain marks painted on the forehead or other parts of the body.

The first three of the four main castes, that is to say the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaisyas, are distinguished by a thin cord hung across from the left shoulder to the right hip. But this cord is also worn by the Jains and even by the Panchalas, or five castes of artisans, so one is apt to be deceived by it.

From what has been said it will appear that the name of a caste forms after all its best indication. It was thus that the tribes of Israel were distinguished. The names of several of the Hindu castes have a known meaning ; but for the most part they date from such ancient times that it is impossible to find out their significance.

There is yet another division more general than any I have referred to yet, namely, that into Right-hand and Left-hand factions. This appears to be but a modern invention, since it is not mentioned in any of the ancient books of the country ; and I have been assured that it is unknown in Northern India. Be that as it may, I do not believe that any idea of this baneful institution, as it exists at the present day, ever entered the heads of those wise lawgivers who considered they had found in caste distinc- tions the best guarantee for the observance of the laws which they prescribed for the people.

This division into Right-hand and Left-hand factions, whoever invented it, has turned out to be the most direful disturber of the public peace. It has proved a perpetual source of riots, and the cause of endless animosity amongst the natives.

1 Remarriage of virgin widows is one of the foremost planks in the platform of Social Reform, but it is opposed violently by the ortho- dox. — En.

OPPOSITION BETWEEN FACTIONS

Most castes belong either to the Left-hand or Right-hand faction. The former comprises the Vaisyas or trading classes, the Panchalas or artisan classes, and some of the low Sudra castes. It also contains the lowest caste, namely, the Chucklers or leather- workers, who are looked upon as its chief support.

To the Right-hand faction belong most of the higher castes of Sudras. The Pariahs are its chief support, as a proof of which they glory in the title Valangai-Mougattar, or friends of the Right-hand. In the disputes and con- flicts which so often take place between the two factions it is always the Pariahs who make the most disturbance and do the most damage.

The Brahmins, Rajahs, and several classes of Sudras are content to remain neutral, and take no part in these quarrels. They are often chosen as arbiters in the differ- ences which the two factions have to settle between them- selves.

The opposition between the two factions arises from certain exclusive privileges to which both lay claim. But as these alleged privileges are nowhere clearly defined and recognized, they result in confusion and uncertainty, and are with difficulty capable of settlement. In these circum- stances one cannot hope to conciliate both parties ; all that one can do is to endeavour to compromise matters as far as possible.

When one faction trespasses on the so-called rights of the other, tumults arise which spread gradually over large tracts of territory, afford opportunity for excesses of all kinds, and generally end in bloody conflicts. The Hindu, ordinarily so timid and gentle in all other circumstances of life, seems to change his nature completely on occasions like these. There is no danger that he will not brave in maintaining what he calls his rights, and rather than sacrifice a tittle of them he will expose himself without fear to the risk of losing his life.

I have several times witnessed instances of these popular insurrections excited by the mutual pretensions of the two

factions and pushed to such an extreme of fury that the presence of a military force has been insufficient to quell them, to allay the clamour, or to control the excesses in which the contending factions consider themselves entitled to indulge.

RIOTOUS DISTURBANCES

Occasionally, when the magistrates fail to effect a re- conciliation by peaceful means, it is necessary to resort to force in order to suppress the disturbances. I have some- times seen these rioters stand up against several discharges of artillery without exhibiting any sign of submission. And when at last the armed force has succeeded in restoring order it is only for a time. At the very first opportunity the rioters are at work again, regardless of the punishment they have received, and quite ready to renew the conflict as obstinately as before. Such are the excesses to which the mild and peaceful Hindu abandons himself when his courage is aroused by religious and political fanaticism.

The rights and privileges for which the Hindus are ready to fight such sanguinary battles appear highly ridiculous, especially to a European. Perhaps the sole cause of the contest is the right to wear slippers or to ride through the streets in a palanquin or on horseback during marriage festivals. Sometimes it is the privilege of being escorted on certain occasions by armed retainers, sometimes that of having a trumpet sounded in front of a procession, or of being accompanied by native musicians at public cere- monies. Perhaps it is simply the particular kind of musical instrument suitable to such occasions that is in dispute ; or perhaps it may be the right of carrying flags of certain colours or certain devices during these ceremonies. Such at any rate are a few of the privileges for which Hindus are ready to cut each other's throats.

It not unfrequently happens that one faction makes an attack on the rights, real or pretended, of the other. There- upon the trouble begins, and soon becomes general if it is not appeased at the very outset by prudent and vigorous measures on the part of the magistracy.

I could instance very many examples bearing on this fatal distinction between Right-hand and Left-hand ; but what I have already said is enough to show the spirit which animates the Hindus in this matter. I once witnessed

PETTY CAUSES OF DISPUTE

a dispute of this nature between the Pariahs and Chuckhrs, or leather-workers. There seemed reason to fear such disastrous consequences throughout the whole district in question, that many of the more peaceful inhabitants began to desert their villages and to carry away their goods and chattels to a place of safety, just as is done when the country is threatened by the near approach of a Mahratta army. However, matters did not reach this extremity. The principal inhabitants of the district opportunely offered to arbitrate in the matter, and they succeeded by diplomacy and conciliation in smoothing away the difficulties and in appeasing the two factions, who were only awaiting the signal to attack each other.

One would not easily guess the cause of this formidable commotion. It simply arose from the fact that a Chuckler had dared to appear at a public ceremony with red flowers stuck in his turban, a privilege which the Pariahs alleged to belong exclusively to the Right-hand faction 1 !

CHAPTER II

Advantages resulting from Caste Divisions. — Similar Divisions amongst many Ancient Nations.

Many persons studyso imperfectly the spirit and character of the different nations that inhabit the earth, and the in- fluence of climate on their manners, customs, predilections, and usages, that they are astonished to find how widely such nations differ from each other. Trammelled by the prejudices of their own surroundings, such persons think nothing well regulated that is not included in the polity and government of their own country. They would like to see all nations of the earth placed on precisely the same footing as themselves. Everything which differs from their own customs they consider either uncivilized or ridiculous.

1 These faction fights have gradually disappeared under the civilizing influences of education and good government ; and if they ever occur at all, are confined to the lowest castes and never spread beyond the limits of a village. The distinctions between the two factions, however, still exist. — Ed.

PREJUDICES AGAINST CASTE

Now, although man's nature is pretty much the same all the world over, it is subject to so many differentiations caused by soil, climate, food, religion, education, and other circumstances peculiar to different countries, that the system of civilization adopted by one people would plunge another into a state of barbarism and cause its complete downfall.

I have heard some persons, sensible enough in other respects, but imbued with all the prejudices that they have brought with them from Europe, pronounce what appears to me an altogether erroneous judgement in the matter of caste divisions amongst the Hindus. In their opinion, caste is not only useless to the body politic, it is also ridi- culous, and even calculated to bring trouble and disorder on the people. For my part, having lived many years on friendly terms with the Hindus, I have been able to study their national life and character closely, and I have arrived at a quite opposite decision on this subject of caste. I believe caste division to be in many respects the chef- d'oeuvre, the happiest effort, of Hindu legislation. I am persuaded that it is simply and solely due to the distribu- tion of the people into castes that India did not lapse into a state of barbarism, and that she preserved and perfected the arts and sciences of civilization whilst most other nations of the earth remained in a state of barbarism. I do not consider caste to be free from many great draw- backs ; but I believe that the resulting advantages, in the case of a nation constituted like the Hindus, more than outweigh the resulting evils.

To establish the justice of this contention we have only to glance at the condition of the various races of men who live in the same latitude as the Hindus, and to consider the past and present status of those among them whose natural disposition and character have not been influenced for good by the purifying doctrines of Revealed Religion. We can judge what the Hindus would have been like, had they not been held within the pale of social duty by caste regulations, if we glance at neighbouring nations west of the Peninsula and east of it beyond the Ganges as far as China. In China itself a temperate climate and a form of government peculiarly adapted to a people unlike any other in the world have produced the same effect as the distinction of caste among the Hindus.

ADVANTAGES OF CASTE

After much careful thought I can discover no other reason except caste which accounts for the Hindus not having fallen into the same state of barbarism as their neighbours and as almost all nations inhabiting the torrid zone. Caste assigns to each individual his own profession or calling ; and the handing down of this system from father to son, from generation to generation, makes it impossible for any person or his descendants to change the condition of life which the law assigns to him for any other. Such an institution was probably the only means that the most clear-sighted prudence could devise for main- taining a state of civilization amongst a people endowed with the peculiar characteristics of the Hindus.

We can picture what would become of the Hindus if they were not kept within the bounds of duty by the rules and penalties of caste, by looking at the position of the Pariahs, or outcastes of India, who, checked by no moral restraint, abandon themselves to their natural propensities. Anybody who has studied the conduct and character of the people of this class — which, by the way. is the largest of any in India 2 — will agree with me that a State consist- ing entirely of such inhabitants could not long endure, and could not fail to lapse before long into a condition of barbarism. For my own part, being perfectly familiar with this class, and acquainted with its natural predilections and sentiments, I am persuaded that a nation of Pariahs left to themselves would speedily become worse than the hordes of cannibals who wander in the vast wastes of Africa, and would soon take to devouring each other.

I am no less convinced that if the Hindus were not kept within the limits of duty and obedience by the system of caste, and by the penal regulations attached to each phase of it, they would soon become just what the Pariahs are, and probably something still worse. The whole country

1 This is true only of Southern India, where the Pariahs number 5,000,000. They form one-seventh of the total population of the Madras Presidency. Of late years the degraded condition of these outcastes has attracted much attention, ami a great deal is now being done to elevate them morally and materially. — Ed.

THE FOUNDATIONS OF CASTE

would necessarily fall into a stale of hopeless anarchy, and, before the present generation disappeared, this nation, so polished under present conditions, would have to be reckoned amongst the most uncivilized of the world. The legislators of India, whoever they may have been, were far too wise and too well acquainted with the natural character of the people for whom they prescribed laws to leave it to the discretion or fancy of each individual to cultivate what knowledge he pleased, or to exercise, as seemed best to him, any of the various professions, arts, or industries which are necessary for the preservation and well-being of a State.

They set out from that cardinal principle common to all ancient legislators, that no person should be useless to the commonwealth. At the same time they recognized that they were dealing with a people who were indolent and careless by nature, and whose propensity to be apathetic was so aggravated by the climate in which they lived, that unless every individual had a profession or employment rigidly imposed upon him, the social fabric could not hold together and must quickly fall into the most deplorable state of anarchy. These ancient lawgivers, therefore, being well aware of the danger caused by religious and political innovations, and being anxious to establish durable and inviolable rules for the different castes comprising the Hindu nation, saw no surer way of attaining their object than by combining in an unmistakable manner those two great foundations of orderly government, religion and politics. Accordingly there is not one of their ancient usages, not one of their observances, which has not some religious principle or object attached to it. Everything, indeed, is governed by superstition and has religion for its motive. The style of greeting, the mode of dressing, the cut of clothes, the shape of ornaments and their manner of adjustment, the various details of the toilette, the archi- tecture of houses, the corners where the hearth is placed and where the cooking pots must stand, the manner of going to bed and of sleeping, the forms of civility and politeness that must be observed : all these are severely regulated.

CASTE IN PALESTINE AND EGYPT

During the many years that I studied Hindu customs, 1 cannot say that I ever observed a single one, however unimportant and simple, and, I may add, however filthy and disgusting, which did not rest on some religious prin- ciple or other. Nothing is left to chance ; everything is laid down by rule, and the foundation of all their customs is purely and simply religion. It is for this reason that the Hindus hold all their customs and usages to be inviolable, for, being essentially religious, they consider them as sacred as religion itself.

And, be it noted, this plan of dividing the people into castes is not confined to the lawgivers of India. The wisest and most famous of all lawgivers, Moses, availed himself of the same institution, as being the one which offered him the best means of governing the intractable and rebellious people of whom he had been appointed the patriarch.

The division of the people into castes existed also amongst the Egyptians. With them, as with the Hindus, the law assigned an occupation to each individual, which was handed down from father to son. It was forbidden to any man to have two professions, or to change his own. Each caste had a special quarter assigned to it, and people of a different caste were prohibited from settling there. Nevertheless there was this difference between the Egyptians and the Hindus : with the former all castes and all pro- fessions were held in esteem ; all employments, even of the meanest kind, were alike regarded as honourable ; and, although the priestly and military castes possessed peculiar privileges, nobody would have considered it anything but criminal to despise the classes whose work, whatever it happened to be, contributed to the general good 1 . With the Hindus, on the other hand, there are professions and callings to which prejudice attaches such degradation that those who follow them are universally despised by those castes which in the public estimation exercise higher functions.

It must here be remarked, however, that the four great professions without which a civilized nation could not exist, namely, the army, agriculture, commerce, and weaving, are held everywhere in the highest esteem. All castes, from the Brahmin to the Pariah, are permitted to follow the first three, and the fourth can be followed by all the principal classes of Sudras 1 .

1 See what the illustrious Bossuet says on this point in his DivcuiM* sur VHistoire UniverseUe, Part III. — Dubois.

CASTE AMONGST ANCIENT NATIONS

These same caste distinctions observable amongst Hindus exist likewise, with some differences, amongst the Arabs and Tartars. Probably, indeed, they were common to the majority of ancient nations. Cecrops, it will be remembered, separated the people of Athens into four tribes or classes, while their great lawgiver, Solon, upheld this distinction and strengthened it in several ways. Numa Pompilius, again, could devise no better way of putting an end to the racial hatred between Sabines and Romans than by separat- ing the body of the people into different castes and classes. The result of his policy was just what he had desired. Both Sabines and Romans, once amalgamated in this manner, forgot their national differences and thought only of those of their class or caste.

Those who instituted the caste system could not but perceive that with nations in an embryonic stage the more class distinctions there are the more order and symmetry there must be, and the more easy it is to exercise control and preserve order. This, indeed, is the result which caste classification amongst the Hindus has achieved. The shame which would reflect on a whole caste if the faults of one of its individual members went unpunished guarantees that the caste will execute justice, defend its own honour, and keep all its members within the bounds of duty. For, be it noted, every caste has its own laws and regulations, or rather, we may say, its own customs, in accordance with which the severest justice is meted out, just as it was by the patriarchs of old.

Thus in several castes adultery is punishable by death 2 . Girls or widows who succumb to temptation are made to suffer the same penalty as those who have seduced them. The largest temple of the town of Conjeeveram, in the Carnatic, an immense building, was constructed, so it is said, by a rich Brahmin who had been convicted of having had illicit intercourse with a low-caste Pariah woman. He was, however, sentenced to this severe penalty, not so much on account of the immorality of his action, seeing that in the opinion of the Brahmins it was not immoral at all, but on account of the low-caste person who had been the partner of his incontinence. There are various kinds of delinquencies in connexion with which a caste may take proceedings, not only against the principal offenders, but against those who have taken any part whatever in them. Thus it is caste authority which, by means of its wise rules and prerogatives, preserves good order, suppresses vice, and saves Hindus from sinking into a state of barbarism.

1 This statement is not quite correct, for in Southern India, at any rate, some classes of Pariahs are most expert weavers, and are honoured as such throughout the country. — Ed.

2 This of course is no longer allowed by law. — Ed.

CASTE PENALTIES

It may also be said that caste regulations counteract to a great extent the evil effects which would otherwise be produced on the national character by a religion that encourages the most unlicensed depravity of morals, as well in the decorations of its temples as in its dogmas and ritual.

In India, where the princes and the aristocracy live in extreme indolence, attaching little importance to making their dependants happy and taking small pains to inculcate in them a sense of right and wrong, there are no other means of attaining these desirable ends and preserving good order than by authoritative rulings of the caste system. The worst of it is, these powers are not suffi- ciently wide, or rather they are too often relaxed. Many castes exercise them with severity in cases that are for the most part frivolous, but display an easy and culpable indulgence towards real and serious delinquencies. On the other hand, caste authority is often a check against abuses which the despotic rulers of the country are too apt to indulge in. Sometimes one may see, as the result of a caste order, the tradesmen and merchants of a whole district closing their shops, the labourers abandoning their fields, or the artisans leaving their workshops, all because of some petty insult or of some petty extortion suffered by some member of their caste ; and the aggrieved people will remain obstinately in this state of opposition until the injury has been atoned for and those responsible for it punished.

PURITY OF HINDI' DESCENT

Another advantage resulting from the caste system is the hereditary continuation of families and that purity of descent which is a peculiarity of the Hindus, and which consists in never mixing the blood of one family or caste with that of another. Marriages are confined to parties belonging to the same family, or at any rate the same caste. In India, at any rate, there can be no room for the reproach, so often deserved in European countries, that families have deteriorated by alliances with persons of low or unknown extraction. A Hindu of high caste can, without citing his title or producing his genealogical tree, trace his descent back for more than two thousand years without fear of contradiction. He can also, without any other passport than that of his high caste, and in spite of his poverty, present himself anywhere ; and he would be more courted for a marriage alliance than any richer man of less pure descent. Nevertheless, it is not to be denied that there are some districts where the people are not quite so particular about their marriages, though such laxity is blamed and held up to shame as an outrage on propriety, while those guilty of it take very good care to conceal it as much as possible from the public.

Further, one would be justified in asserting that it is to caste distinctions that India owes the preservation of her arts and industries. For the same reason she would have reached a high standard of perfection in them had not the avarice of her rulers prevented it. It was chiefly to attain this object that the Egyptians were divided into castes, and that their laws assigned the particular place which each individual should occupy in the commonwealth. Their lawgivers no doubt considered that by this means all arts and industries would continue to improve from generation to generation, for men must needs do well that which they have always been in the habit of seeing done and which they have been constantly practising from their youth.

This perfection in arts and manufactures would un- doubtedly have been attained by so industrious a people as the Hindus, if, as I have before remarked, the cupidity of their rulers had not acted as a check. As a matter of fact, no sooner has an artisan gained the reputation of excelling in his craft than he is at once carried off by order of the sovereign, taken to the palace, and there confined for the rest of his life, forced to toil without remission and with little or no reward. Under these circumstances, which are common to all parts of India under the government of native princes, it is hardly surprising that every art and industry is extinguished and all healthy competition deadened. This is the chief and almost the only reason why progress in the arts has been so slow among the Hindus, and why in this respect they are now far behind other nations who did not become civilized for many cen- turies after themselves.

HINDU ARTS AND MANUFACTURES

Their workmen certainly lack neither industry nor skill. In the European settlements, where they are paid according to their merit, many native artisans are to be met with whose work would do credit to the best artisans of the West. Moreover they feel no necessity to use the many European tools, whose nomenclature alone requires special study. One or two axes, as many saws and planes, all of them so rudely fashioned that a European workman would be able to do nothing with them — these are almost the only instruments that are to be seen in the hands of Hindu carpenters. The working materials of a journeyman gold- smith usually comprise a tiny anvil, a crucible, two or three small hammers, and as many files. With such simple tools the patient Hindu, thanks to his industry, can produce specimens of work which are often not to be distinguished from those imported at great expense from foreign countries. To what a standard of excellence would these men have attained if they had been from the earliest times subjected to good masters !

In order to form a just idea of what the Hindus would have done with their arts and manufactures if their natural industry had been properly encouraged, we have only to visit the workshop of one of their weavers or of one of their printers on cloth and carefully examine the instru- ments with which they produce those superb muslins, those superfine cloths, those beautiful coloured piece-goods, which are everywhere admired, and which in Europe occupy a high place among the principal articles of adornment. In manufacturing these magnificent stuffs the artisan uses

COHESION OF CASTE COMMUNITIES

his feet almost as much as his hands. Furthermore the weaving loom, and the whole apparatus for spinning the thread before it is woven, as well as the rest of the tools which he uses for the work, are so simple and so few that altogether they would hardly comprise a load for one man. Indeed it is by no means a rare sight to see one of these weavers changing his abode, and carrying on his back all that is necessary for setting to work the moment he arrives at his new home.

Their printed calicoes, which are not less admired than their muslins, are manufactured in an equally simple manner. Three or four bamboos to stretch the cloth, as many brushes for applying the colours, with a few pieces of potsherd to contain them, and a hollow stone for pounding them : these are pretty well all their stock in trade.

I will venture to express one other remark on the political advantages resulting from caste distinctions. In India parental authority is but little respected : and parents, overcome doubtless by that apathetic indifference which characterizes Hindus generally, are at little pains, as I shall show later on, to inspire those feelings of filial reverence which constitute family happiness by enchaining the affec- tions of the children to the authors of their existence. Outward affection appears to exist between brothers and sisters, but in reality it is neither very strong nor very sincere. It quickly vanishes after the death of their parents, and subsequently, we may say, they only come together to fight and to quarrel. Thus, as the ties of blood relationship formed so insecure a bond between different members of a community, and guaranteed no such mutual assistance and support as were needed, it became necessary to bring families together in large caste communities, the individual members of which had a common interest in protecting, supporting, and defending each other. It was thus that the links of the Hindu social chain were so strongly and ingeniously forged that nothing was able to break them.

CASTE SENTENCES

This was the object which the ancient lawgivers of India attained by establishing the caste system, and they thereby acquired a title to honour unexampled in the history of the world. Their work lias stood the test of thousands of years, and lias survived the lapse of time and the many revolutions to which this portion of the globe has been subjected. The Hindus have often passed beneath the yoke of foreign invaders, whose religions, laws, and customs have been very different from their own ; yet all efforts to impose foreign institutions on the people of India have been futile, and foreign occupation has never dealt more than a feeble blow against Indian custom. Above all, and before all, it was the caste system which protected them. Its authority was extensive enough to include sentences of death, as I have before remarked. The story is told, and the truth of it is incontestable, that a man of the Rajput caste was a few years ago compelled by the people of his own caste and by the principal inhabitants of his place of abode to execute, with his own hand, a sentence of death passed on his daughter. This unhappy girl had been dis- covered in the arms of a youth, who would have suffered the same penalty had he not evaded it by sudden flight.

Nevertheless, although the penalty of death may be inflicted by some castes under certain circumstances, this form of punishment is seldom resorted to nowadays. When- ever it is thought to be indispensable, it is the father or the brother who is expected to execute it, in secrecy. Generally speaking, however, recourse is had by prefer- ence to the imposition of a fine and to various ignominious corporal punishments. As regards these latter, we may note as examples the punishments inflicted on women w T ho have forfeited their honour, such as shaving their heads, compelling them to ride through the public streets mounted on asses and with their faces turned towards the tail, forcing them to stand a long time with a basket of mud on their heads before the assembled caste people, throwing into their faces the ordure of cattle, breaking the cotton thread of those possessing the right to wear it, and ex- communicating the guilty from their caste \

1 The infliction of such punishments might nowadays be followed by prosecution in the Civil and Criminal Courts. — Ed.

CHAPTER III

Expulsion from Caste. — Cases in which such Degradation is inflicted. — By whom inflicted. — Restoration to Caste. — Methods of effecting it.

Of all kinds of punishment the hardest and most un- bearable for a Hindu is that which cuts him off and expels him from his caste. Those whose duty it is to inflict it are the gurus, of whom I shall have more to say in a sub- sequent chapter, and, in default of them, the caste headmen. These latter are usually to be found in every district, and it is to them that all doubtful or difficult questions affecting the caste system are referred. They call in, in order to help them to decide such questions, a few elders who are versed in the intricacies of the matters in dispute.

This expulsion from caste, which follows either an in- fringement of caste usages or some public offence calculated if left unpunished to bring dishonour on the whole com- munity, is a kind of social excommunication, which deprives the unhappy person who suffers it of all intercourse with his fellow-creatures. It renders him, as it were, dead to the world, and leaves him nothing in common with the rest of society. In losing his caste he loses not only his relations and friends, but often his wife and his children, who would rather leave him to his fate than share his disgrace with him. Nobody dare eat with him or even give him a drop of water. If he has marriageable daughters nobody asks them in marriage, and in like manner his sons are refused wives. He has to take it for granted that wherever he goes he will be avoided, pointed at with scorn, and regarded as an outcaste.

If after losing caste a Hindu could obtain admission into an inferior caste, his punishment would in some degree be tolerable ; but even this humiliating compensation is denied to him. A simple Sudra with any notions of honour and propriety would never associate or even speak with a Brahmin degraded in this manner. It is necessary, there- fore, for an outcaste to seek asylum in the lowest caste of Pariahs if he fail to obtain restoration to his own ; or else he is obliged to associate with persons of doubtful caste. There are always people of this kind, especially in the quarters inhabited by Europeans; and unhappy is the man who puts trust in them ! A caste Hindu is often a thief and a bad character, but a Hindu without caste is almost always a rogue.

EXPULSION FROM CASTE

Expulsion from caste is generally put in force without much formality. Sometimes it is due merely to personal hatred or caprice. Thus, when persons refuse, without any apparent justification, to attend the funeral or marriage ceremonies of their relations or friends, or when they happen not to invite the latter on similar occasions, the individuals thus slighted never fail to take proceedings in order to obtain satisfaction for the insult offered to them, and the arbitrators called in to decide the case usually pass a decree of excommunication. When a case is thus settled by arbitration, however, a sentence of excommunication does not bring upon the guilty person the same disgrace and the same penalties which are the lot of those whose offence offers no room for compromise.

Otherwise it matters little whether the offence be deli- berate, whether it be serious or trivial, in determining that a person shall pay this degrading penalty. A Pariah who concealed his origin, mixed with other Hindus, entered their houses and ate with them without being recognized, would render those who had thus been brought into con- tact with him liable to ignominious expulsion from their caste. At the same time a Pariah guilty of such a daring act would inevitably be murdered on the spot, if his enter- tainers recognized him.

A Sudra, too, who indulged in illicit intercourse witli a Pariah woman would be rigorously expelled from caste if his offence became known.

A number of Brahmins assembled together for some family ceremony once admitted to their feast, without being aware of it, a Sudra who had gained admittance on the false assertion that he belonged to their caste. On the circumstance being discovered, these Brahmins were one and all outcasted, and were unable to obtain reinstatement until they had gone through all kinds of formalities and been subjected to considerable expense.

INSTANCES OF CASTE VIOLATION

I once witnessed amongst the Gollavarus, or shepherds, an instance of even greater severity. A marriage had been arranged, and, in the presence of the family concerned, certain ceremonies which were equivalent to betrothal amongst ourselves had taken place. Before the actual celebration of the marriage, which was fixed for a con- siderable time afterwards, the bridegroom died. The parents of the girl, who was very young and pretty, there- upon married her to another man. This was in direct violation of the custom of the caste, which condemns to perpetual widowhood girls thus betrothed, even when, as in this case, the future bridegroom dies before marriage has been consummated. The consequence was that all the persons who had taken part in the second ceremony were expelled from caste, and nobody would contract marriage or have any intercourse whatever with them. A long time afterwards I met several of them, well advanced in age, who had been for this reason alone unable to obtain husbands or wives, as the case might be.

Let me relate another instance. Eleven Brahmins travelling in company were obliged to cross a district devastated by war. They arrived hungry and tired in a village, which, contrary to their expectations, they found deserted. They had with them a small quantity of rice, but they could find no other pots to boil it in than some which had been left in the house of the village washerman. To touch these would constitute in the case of Brahmins an almost ineffaceable defilement. Nevertheless, suffering from hunger as they were, they swore mutual secrecy, and after washing and scouring the pots a hundred times they prepared their food in them. The rice was served and the repast consumed by all but one, who refused to partake of it, and who had no sooner returned home than he pro- ceeded to denounce the ten others to the chief Brahmins of the village. The news of such a scandal spread quickly, and gave rise to a great commotion amongst all classes of the inhabitants. An assembly was held. The delinquents were summoned and forced to appear. Warned before- hand, however, of the proceedings that were to be in- stituted against them, they took counsel together and agreed to answer unanimously, when called upon to explain, that it was the accuser himself who had committed the heinous sin and who had imputed it to them falsely and maliciously. The testimony of ten persons was calculated to carry more weight than that of one. The accused were consequently acquitted, while the accuser alone was igno- niiniously expelled from caste by the headmen, who, though they were perfectly sure of his innocence, were indignant at his treacherous disclosure.

ATTACHMENT TO CASTE

From what has been said, it will no longer be surprising to learn that Hindus are as much, nay, even more, attached to their caste than the gentry of Europe are to their rank. Prone to using the most disgustingly abusive language in their quarrels, they nevertheless easily forgive and forget such insulting epithets ; but if one should say of another that he is a man without caste, the insult would never be forgiven or forgotten.

This strict and universal observance of caste and caste usages forms practically their whole social law. A very great number of people are to be found amongst them, to whom death would appear far more desirable than life, if, for example, the latter were sustained by eating cow's flesh or any food prepared by Pariahs and outcastes.

It is this same caste feeling which gives rise to the con- tempt and aversion which they display towards all foreign nations, and especially towards Europeans, who, being as a rule but slightly acquainted with the customs and pre- judices of the country, are constantly violating them. Owing to such conduct the Hindus look upon them as barbarians totally ignorant of all principles of honour and good breeding.

In several cases, at least, restoration to caste is an impossibility. But when the sentence of excommunication has been passed merely by relations, the culprit conciliates the principal members of his family and prostrates himself in a humble posture, and with signs of repentance, before his assembled castemen. He then listens without com- plaint to the rebukes which are showered upon him, receives the blows to which he is oftentimes condemned, and pays the fine which it is thought fit to impose upon him. Finally, after having solemnly promised to wipe out by good con- duct the taint resulting from his degrading punishment, he sheds tears of repentance, performs the sasktanga before the assembly, and then serves a feast to the persons present.

THE 'SASHTANGA'

When all this is finished lie is looked upon as reinstated.

The sashta?iga, by the way, is a sign or salute expressing humility, which is not only recognized amongst the Hindus and other Asiatic nations, but was in use amongst more ancient peoples. Instances of it are quoted in Scripture, where this extraordinary mark of respect is known as adoration, even when it is paid to simple mortals. {Vide Genesis xviii. 2 ; xix. 1 ; xxxiii. 3 ; xlii. 6 ; xliii. 26 ; 1. 18, &c, &c.) In the same way the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and other nations mentioned in Holy Writ were acquainted with this method of reverent salutation and observed it under the same circumstances as the Hindus. As I shall often have occasion in this work to mention the sashtanga 1 will give here a definition of it. The person who performs it lies prostrate, his face on the ground and his arms ex- tended beyond his head. It is called sashtanga from the prostration of the six members, because, when it is performed, the feet, the knees, the stomach, the chest, the forehead, and the arms must touch the earth. It is thus that pro- strations are made before persons of high degree, such as princes and priests. Children sometimes prostrate them- selves thus before their fathers. It is by no means rare to see Sudras of different classes performing sashtanga before Brahmins ; and it often happens that princes, before engaging an enemy, thus prostrate themselves before their armies drawn up in battle array \

When expulsion from caste is the result of some heinous offence, the guilty person who is readmitted into caste has to submit to one or other of the following ordeals : his tongue is slightly burnt with a piece of heated gold ; he is branded indelibly on different parts of his body with red- hot iron ; he is made to walk barefooted over red-hot embers ; or he is compelled to crawl several times under the belly of a cow. Finally, to complete his purification, he is made to drink the pancha-gavia. These words, of which a more detailed explanation will be given later on, signify literally the five things or substances derived from the

1 Here and elsewhere the Abbe makes the mistake of interpreting saslUanga to mean ' the six angas,' or ' parts of the body.' Sashtanga (Saashtanga) really means with the eight jxirt* of the body, which are the two hands, the two feet, two knees, forehead, and breast. — Ed

UNPARDONABLE SINS OE CASTE

body of a cow ; namely, milk, curds, ghee (clarified butter), dung and urine, which are mixed together. The last- named, urine, is looked upon as the most efficacious for purifying any kind of uncleanness. I have often seen superstitious Hindus following the cows to pasture, waiting for the moment when they could collect the precious liquid in vessels of brass, and carrying it away while still warm to their houses. I have also seen them waiting to catch it in the hollow of their hands, drinking some of it and rubbing their faces and heads with the rest. Rubbing it in this way is supposed to wash away all external uncleanness, and drinking it to cleanse all internal impurity. When this disgusting ceremony of the pa?icha-gavia is over, the person who has been reinstated is expected to give a great feast to the Brahmins who have collected from all parts to witness it. Presents of more or less value are also expected by them, and not until these are forthcoming does the guilty person obtain all his rights and privileges again.

There are certain offences so heinous in the sight of Hindus, however, as to leave no hope of reinstatement to those who commit them. Such, for example, would be the crime of a Brahmin who had openly cohabited with a Pariah woman. Were the woman of any other caste, I believe that it would be possible for a guilty person, by getting rid of her and by repudiating any children he had had by her, to obtain pardon, after performing many purifying ceremonies and expending much money. But hopeless would be the case of the man who under any circumstances had eaten of cow's flesh. There would be no hope of pardon for him, even supposing he had com- mitted such an awful sacrilege under compulsion.

It would be possible to cite several instances of strange and inflexible severity in the punishment of caste offences. When the last Mussulman Prince reigned in Mysore and sought to proselytize the whole Peninsula, he began by having several Brahmins forcibly circumcised, compelling them afterwards to eat cow's flesh as an unequivocal token of their renunciation of caste. Subsequently the people were freed from the yoke of this tyrant, and many of those who had been compelled to embrace the Mahomedan religion made every possible effort, and offered very large sums, to be readmitted to Hinduism. .Assemblies were held in different parts of the country to thoroughly consider their cases. It was everywhere decided that it was quite possible to purify the uncleanness of circumcision and of intercourse with Mussulmans. But the crime of eating cow's flesh, even under compulsion, was unanimously declared to be irredeemable and not to be effaced either by presents, or by fire, or by the pancha-gavia.

THE 'UNPARDONABLE SIN' OF HINDUISM

A similar decision was given in the case of Sudras who found themselves in the same position, and who, after trying all possible means, were not more successful. One and all, therefore, were obliged to remain Mahomedans.

A Hindu, of whatever caste, who has once had the misfortune to be excommunicated, can never altogether get rid of the stain of his disgrace. If he ever gets into trouble his excommunication is always thrown in his teeth.

CHAPTER IV

Antiquity and Origin of Caste.

Apparently there is no existing institution older than the caste system of the Hindus. Greek and Latin authors who have written about India concur in thinking that it has been in force from time immemorial ; and certainly the unswerving observance of its rules seems to me an almost incontestable proof of its antiquity \ Under a solemn and unceasing obligation as the Hindus are to respect its usages, new and strange customs are things unheard of in their country. Any person who attempted to introduce such innovations would excite universal resentment and opposi- tion, and would be branded as a dangerous person.

1 Dr. Muir, in Old Sanskrit Texts, vol. i. p. 159, reviewing the texts which he had cited on this subject, says : — ' First, we have the set of accounts in which the four castes are said to have sprung from pro- genitors who were separately created ; but in regard to the manner of their creation we find the greatest diversity of statement. The most common story is that the castes issued from the mouth, arms, thighs, and feet of Purusha, or Brahma. The oldest extant passage in which this idea occurs, and from which all the later myths of a similar tenor have no doubt been borrowed, is to be found in the Purusha Sukta ; but it is doubtful whether, in the form in which it is there represented, this representation is anything more than an allegory. In some of the texts from the Bhagavata Purana traces of the same allegorical character may be perceived ; but in Manu and the Puranas the mystical import of the Yedic text disappears, and the figurative narration is hardened into a literal statement of fact. In the chapters of the Vishnu, Vayu, and Miirkandeya Puranas, where castes arc described as coeval with

CASTE IN THE PURANAS

creation, and as having been naturally distinguished by different guruu, or qualities, involving varieties of moral character, we are nevertheless allowed to infer that those qualities exerted no influence on the classes in which they were inherent, as the condition of the whole race during the Krita age is described as one of uniform perfection and happiness ; while the actual separation into castes did not take place, according to the Vayu Purana, until men had become deteriorated in the Treta age.

' Second, in various passages from the Brahmanas epic poems, and Puranas, the creation of mankind is described without the least allusion to any separate production of the progenitors of the four castes. And whilst in the chapters where they relate the distinct formations of the tastes, the Puranas assign different natural dispositions to each class, they elsewhere represent all mankind as being at the creation uniformly distinguished by the quality of passion. In one text men are said to be the offspring of Vivasat ; in another his son Mami is said to be their progenitor, whilst in a third they are said to be descended from a female of the same name. The passage which declares Manu to have been the father of the human race explicitly affirms that men of all the four castes were descended from him. In another remarkable text the Mahabharata categorically asserts that originally there was no distinction of classes, the existing distribution having arisen out of differences of character and occupation. In these circumstances, we may fairly conclude that the separate origination of the four castes was far from being an article of belief universally received by Indian antiquity.'

The following is the categorical assertion in the Mahabharata (Santi parvan) above referred to. It occurs in the course of a discussion on caste between Bhrigu and Bharadwaja. Bhrigu, replying to a question put by Bharadwaja, says: 'The colour [varna) of the Brahmins was white ; that of the Kshatriyas red ; that of the Vaisyas yellow, and that of the Sudras black.' Bharadwaja here rejoins, * If the caste {varna) of the four classes is distinguished by their colour {varna), then a confusion of all the castes is observable. . . .' Bhrigu replies, ' There is no differ- ence of castes : this world, having been at hist created by Brahma entirely Brahmanic, became (afterwards) separated into tastes in con- sequence of works. Those Brahmins (lit. twice-born men) who were fond of sensual pleasure, fiery, irascible, prone to violence, who had forsaken their duty and were red limbed, fell into the condition of Kshatriyas. Those Brahmins who derived their livelihood from kine, who were yellow, who subsisted by agriculture, and who neglected to practise their duties, entered into the state of Vaisyas. Those Brahmins who wen- addicted to mischief and falsehood, who were COVetoUS, who lived by all kinds of work, who were black and had fallen from purity, sank into the condition of Sudras.' — Ed.

ANTIQUITY OF CASTE CEREMONIES

The task, however, would be such a difficult one that I can hardly believe that any proposal of the kind would ever enter an intelligent person's head. Everything is always done in exactly the same way ; even the minutest details are invested with a solemn importance of their own, because a Hindu is convinced that it is only by paying rigorous attention to small details that more momentous concerns are safeguarded. Indeed, there is not another nation on earth which can pride itself on having so long preserved intact its social customs and regulations.

The Hindu legislators of old had the good sense to give stability to these customs and regulations by associating with them many outward ceremonies, which, by fixing them in the minds of the people, ensured their more faithful observance. These ceremonies are invariably observed, and have never been allowed to degenerate into mere forms that can be neglected without grave consequences. Failure to perform a single one of them, however unimpoitant it might appear, would never go unpunished.

One cannot fail to remark how very similar some of these ceremonies are to those which were performed long ago amongst other nations. Thus the Hindu precepts about cleanness and uncleanness, as also the means em- ployed for preserving the one and effacing the other, are similar in many respects to those of the ancient Hebrews. The rule about marrying in one's caste, and even in one's family, was specifically imposed upon the Jews in the laws which Moses gave them from God \ This rule, too, was in force a long time before that, for it appears to have been general amongst the Chaldeans. We find also in Holy Writ that Abraham espoused his niece, and that the holy patriarch sent into a far country for a maiden of his own family as a wife for his son Isaac. Again, Isaac and his wife Rebecca found it difficult to pardon their son Esau for marrying amongst strangers, that is, amongst the Canaanites ; and they sent their son Jacob away into a distant land to seek a wife from amongst their own people.

In the same way to-day, Hindus residing in a foreign country will journey hundreds of leagues to their native land in search of wives for their sons.

1 Numbers xxxvi. 5-12.

TRADITIONAL ORIGIN OF CASTE

Again, as to the caste system, Moses, as is well known, established it amongst the Hebrews in accordance with the commands of God. This holy lawgiver had, during his long sojourn in Egypt, observed the system as estab- lished in that country, and had doubtless recognized the good that resulted from it. Apparently, in executing the divine order with respect to it he simply adapted and per- fected the system which was in force in Egypt.