Buddhism - The Concept of Anatta or Not Self

There are three different views of the ego or Self. The first is the belief in Self as the soul-entity. The second is the view of the Self based on conceit and pride. The third is the Self as a conventional term for the first-person singular as distinct from other persons. The Self or "I" implicit in "I walk" has nothing to do with illusion or conceit. It is a term of common usage that is to be found in the sayings of the Buddha and arahants. — Discourse on the Ariyavasa Sutta.

Anatta or the Not-Self is a very important concept of Buddhism, which distinguishes it from other religions such as Hinduism and Jainism. In the following discussion, we discuss the concept of Anatta in Buddhism, its importance to the Eightfold Path and the meditative practices of Buddhism, and its possible origins in ancient India before the Buddha.

Anatta means

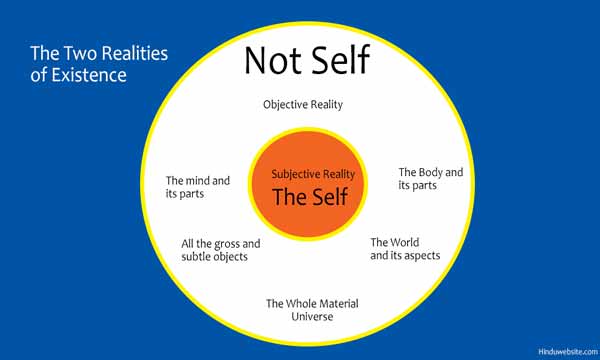

Anatta is the Pali or the crude version of the Sanskrit word, Anatma, meaning Not-Self. It is also often called the Non Self or No Self. Anatta refers to the absence of Self (ana + atma). Anatta also means objective reality or what is not Self or what is other than the Self. Anatta represents all that exists outside the Self or other than the Self.

The roots of Anatta or Anatma are not in Buddhism or in the teachings of the Buddha, but in the ascetic traditions of Hinduism and Jainism of ancient India. It is also not specific to Buddhism only. The Buddha made it popular by making it the central aspect of his teachings. In the belief systems of ancient India, especially those of Hinduism and Jainism, Anatta represented the objective or perceptual aspect of the existential reality. It also represented the outward approach or the perceptual, mindful approach to achieve liberation, in contrast to the inward, witness approach or the withdrawal approach to experience the subjective Self (Atma or Atman).

Anatta as Not-self

The Buddha taught the nonexistence of eternal Souls in the beings. He held that the eternal Self was an illusion, a notion or a formation of the mind. It had no basis in reality. According to him, the world was bereft of a soul (or God), and so was the case with the microcosm of any living being. It was neither possible nor believable that an eternal, imperishable and stable soul could exist anywhere or in any being, when a mere observation showed that beings were subject to change, aging, decay and death. All sentient beings, and even the objects were in the process of becoming and changing from one state to another.

The only Self that made sense to him was the objective self, which could be identified with a name and form and possessed a physical Self, and which was made up of the mind and body. The physical self, or beingness (Anatta or Not-self), was neither eternal nor imperishable nor subjective, but was a part of the objective reality (anatta) only, which could be objectified as a person, but could still be subjectively viewed in its entirety as well as in its parts. Thus, the Anatta was a formation, created by the aggregates of thoughts, memories, desires, expectations, compassion, attachment, illusion and egoism. It was temporary, perishable and changeable. Beyond that objective reality of Anatta, there was nothing else such as a permanent, unchanging, eternal Self.

As part of his teaching, the Buddha discouraged speculation upon any phenomena, which were not part of the perceptual reality. Accordingly, he discouraged questions and speculation upon the nature of the transcendental Self or God. He also avoided speculation upon the nature of Anatta reality, whether it was real or illusory, just as he avoided elaborating the state of Nirvana because it too was outside the boundaries of ordinary human experience.

In a sermon delivered to his first five disciples (Samyutta-Nikaya 22.59), the Buddha provided a clear reasoning in favor of his No-Self argument and advised them to renounce all sense of ownership and possessiveness to end attachment, suffering and the process of becoming. He told them the following.

"O monks, the well-instructed noble disciple, seeing thus, gets wearied of form, gets wearied of feeling, gets wearied of perception, gets wearied of mental formations, gets wearied of consciousness. Being wearied he becomes passion-free. In his freedom from passion, he is emancipated. Being emancipated, there is the knowledge that he is emancipated. He knows: 'birth is exhausted, lived is the holy life, what had to be done is done, there is nothing more of this becoming.'"

On another occasion, as recorded in the same text, he explained the concept of Anatta to another disciple. When he was asked what Anatta meant, he replied thus.

“Just this, Radha, form is not the Self (anatta), sensations are not the Self (anatta), perceptions are not the Self (anatta), assemblages are not the Self (anatta), consciousness is not the Self (anatta). Seeing thusly, this is the end of birth, the Brahman life has been fulfilled, what must be done has been done."

In short, what the Buddha meant was that the body was not the (eternal) Self, the mind was not the Self, the feelings were not the Self, or anything possessed by them was not the Self. The notion of Self, the belief that something was mine or yours, was a mere illusion, which arose from the coming together of aggregates and the formation of a personality and its consciousness. The consciousness itself was a formation of thoughts, feelings, emotions, sensations, memory, reason and intelligence. By observing them and understanding their movements, one could resolve suffering and attain peace and equanimity.

Anatta as the objective reality

Anatta means not only Not-self but also the objective or the perceptual reality which we experience through the mind and the body. It is the reality, which is not the Self or other than the Self or has no relation whatsoever with the Self. Whether the Self exists or not is immaterial. Whatever the mind and body experiences including the world in which they reside constitute the Anatta or the Anatta reality.

The Anatta, objective and the Atma, subjective realities

The Anatta, objective and the Atma, subjective realities

The religions of India fall into Atma and Anatma traditions. They are also referred to as Asti (Is) and Nasti (Is not). Hinduism and Jainism are Atmic traditions. They believe in the existence of eternal souls and in their subjective reality, which is pure, transcendental, self-existing, indefinable, indescribable, indestructible, all knowing, and infinite. The souls are also beyond the mind and senses. Hence, they cannot be experienced in the wakeful state.

The soul or the Self cannot be experienced in deep sleep state also since the mind remains covered in tamas when a person is asleep. It can be experienced only when the mind and the senses are fully withdrawn and absorbed in the contemplation of the Self. Since, it is subjective, the Self cannot be objectified by any means, except notionally or theoretically for our study and understanding.

In contrast, Buddhism is a non-atmic tradition. It does not believe in the pure subjective reality which can exist without any relationship to our experience of the world. If it is, it serves no purpose in resolving our suffering, because our suffering does not arise from the unknown Self, but from the known world. It is the source of karma and the cause of our suffering.

The Anatta strategy

Because of their fundamental doctrinal differences, Buddhism and Hinduism follow divergent strategies to deal with human suffering. Buddhism relies upon Anatta reality and Hinduism upon the Atma reality. Hence they fundamentally differ with regard to their methods to discipline the mind and body and cultivate discernment to achieve liberation. Buddhism relies upon the outward, mindfulness strategy to see the objects of the mind, the body and the world with greater clarity and intelligence to identify the causes of bondage and suffering, while Hinduism recommends the inward, contemplative and restful approach in which the mind and body are withdrawn from the objective reality and silenced to experience self-absorption (Samadhi).

While Hinduism aims to shut down the mind and body from the causes of suffering, Buddhism attempts to face them and understand them with the Anatta approach or strategy, by accepting the objective reality as the starting point for the practice of the Eightfold Path. It is a confrontational approach, but true to the teachings of the Buddha, with gentleness, compassion and nonviolence. With right perception, right thinking and right views, it dwells upon the known rather than the unknown, and looks for solutions within the human experience rather than outside it. The Buddhists do not believe that there can be a subjective reality which is independent of the being or beyond the mind and senses. Even if it exists, there is no proof that it is the cause of suffering.

Existential suffering is produced by the existence of things and causes or the objective reality. Logically, it is better to begin with the known rather than the unknown to resolve existential suffering, and look for viable solutions in the current reality of the present moment rather than in some metaphysical notion of an inexplicable state that cannot humanly be experienced when the mind is active and awake. The Buddhists, therefore, remain wide awake and mindful of their suffering as well as their goal of Nirvana. They may renounce the worldly life, but do not escape from it.

The Four Noble truths unambiguously trace human suffering to the existential reality (Anatta) in which beings are caught. Anatta is amorphous. When people become involved with it through their senses, they develop desires and become bound to the cycle of births and deaths. Anatta is alluring enough to consume our attention and involvement. However, it is also like a honey-trap, which binds the beings to Samsara, or the cycle of births and deaths. When people cling to the world and its objects through attraction and aversion, they become bound to the mortal world and invite suffering into their lives. By engaging in desire-ridden actions, they incur karma and thereby become bound to the cycle of births and deaths.

With this understanding, the Buddha advised monks to observe the objective reality (Anatta) with mindfulness and discernment to see how it caused desires and attachments and produced suffering. This was in sharp contrast to the approach followed in Hinduism and Jainism where the emphasis was upon withdrawing from the objective reality and remaining focused on the Self to experience the purely subjective, omniscient state of the transcendental Self.

Buddhism wholeheartedly accepts the Anatta approach, without any ambivalence, and urges its followers to face the reality rather than engaging in speculations about it, or shutting down their minds and senses to it. It is a very practical, psychoanalytical and down to earth religion, which relies upon intelligence (Buddhi) rather than divine intervention to deal with the problems and the suffering people face. It firmly holds that one cannot resolve suffering by escaping from it or putting the mind to sleep, but by becoming more aware, awake and mindful of its causes and avoiding all possible mistakes that lead to them by right living on the Eightfold Path. One may speculate upon the Self and its reality, but it is an intellectual effort or an elitist approach, which does not mitigate suffering other than giving some people the smug satisfaction that they engaged their minds in higher thinking.

Anatta as impermanence

The Buddha taught not only the Not-self approach to observe oneself but also the impermanence of the personality. He advised his followers not to identify themselves with their names and forms (nama rupa) or their Anatta reality, but become aware of the different aspects of their minds and bodies to know how they produced suffering. By knowing that they were mere aggregates of mental and physical objects and understanding the objective reality (anatta) within them and around them, they could overcome their desires and clinging and come to terms with their suffering and their seeking and striving.

In Buddhist parlance, every living being is just like a river, which is ever changing. Since it flows continuously, one may outwardly see the same river, with the same twists and turns. However, it is never the same because its water is continuously replaced by the water flowing from behind. Over a long period, the river itself may change course, or dry up completely, due to the changes in the climate or environment.

Our consciousness is similar to the river, and our bodies are similar to the earth which supports the rivers. Just as the rivers, our consciousness is always in a state of flux, moving and changing. When a monk realizes that change and impermanence characterize our existence, he is no more troubled by what happens to him, what changes in him or what he gains or loses. He becomes equal to the happenings in his mind and body as well as in the world. Having discerned the truth about himself and the world, he attains peace and equanimity, which in Buddhism, is called the state of Nirvana.

From the teachings of the Buddha we understand that if you study the individual components of a being and if you separate each of them, you will realize that nothing exists beyond them, which is permanent and stable. The personality or the beingness is like a bubble. It is an aggregate of many individual components, which are held together by desires and essential nature. If you separate them, can you say that the individual still exists?

The notion of Self is not only an illusion but also an obstacle to the realization of Nirvana or knowing the truth about oneself. A person or his beingness is created by the aggregates of memories, feelings, perceptions, emotions, etc. Depending upon which of them the person chooses to define himself, the person becomes distinguished or acquires distinctive traits and characteristics which separate him from the rest.

If those choices or components are changed, a different personality emerges from the same person. We know from experience that people do not hold the same thoughts or feelings or emotions always. Hence, they act differently in different circumstances and remain unpredictable. The same happens when a person loses his mind or suffers from amnesia. He becomes a different person with a different personality. From an existential point of view, the objective Self (self-image) is one’s own creation or formation. It is an objective reality which can be perceived, altered, influenced or silenced.

Anatta as emptiness

The essence of Anatta is emptiness. Anatta is the objective experience of the formation and aggregation of things. Nothing is permanent there and nothing there lasts forever. It is like the clouds in the sky or the colors that manifest before the sunset. It exists as long as the mind and the senses exist. When the personality is dissolved, the Anatta which is dependent on it also dissolves. Sister Khema 1 explains the Anatta state from the perspective of Nirvana in the following words.

"The Non-Self is experienced through the aspect of impermanence, through the aspect of unsatisfactoriness, and through the aspect of emptiness. Empty of what? The word ‘emptiness’ is so often misunderstood because when one only thinks of it as a concept, one says ‘what do you mean by empty?’ Everything is there: there are the people, and there are their insides, guts and their bones and blood and everything is full of stuff — and the mind is not empty either. It's got ideas, thoughts and feelings. And even when it doesn't have those, what do you mean by emptiness? The only thing that is empty is the emptiness of an entity. There is no specific entity in anything. That is emptiness. That is the nothingness. That nothingness is also experienced in meditation. It is empty, it is devoid of a specific person, devoid of a specific thing, devoid of anything which makes it permanent, devoid of anything which even makes it important. The whole thing is in flux. So the emptiness is that. And the emptiness is to be seen everywhere; to be seen in oneself. And that is what is called anatta, non-Self. Empty of an entity. There is nobody there. It is all imagination. At first that feels very insecure."

Suggestions for Further Reading

- Buddhism - The Concept of Anatta or No Self

- Anatta and Rebirth or Reincarnation

- What Anatta or No-Self is All About

- Why The Buddha Taught the Anatta or Not-Self Doctrine

- The Right Approach to the Anatta or Not-Self Doctrine

- Anicca or Anitya in Buddhism

- The Agendas of Mindfulness

- The Five Aggregates A Study Guide

- The Working of Maya or Illusion - A Buddhist Perspective

- Respect in Buddhist Thought and Practice

- Buddhism and the Need For Security

- Buddhism - Meditation Upon the Body

- The Buddhist Meditation

- Buddhism - Stages in the Practice of Dhamma

- Anapanasati Sutta Mindfulness of Breathing

- Buddhism - Talks on the Training of the Mind

- The Buddha's Teaching on Right Mindfulness

- The Meaning and Practice of Mindfulness

- Buddhism - Vinaya or Monastic Discipline

- Right Conduct For Lay Buddhists

- Nirvana or Nibbana in Buddhism

- Buddhism - Objects of Meditation and Subjects for Meditation

- Buddhism - Right Speech and Mind Training

- Buddhism - Right Living On The Eightfold Path

- Handbook for the Relief of Suffering by Ajaan Lee

- Theravada Buddhism

- Meat Eating or Vegetarianism in Buddhism

- Essays On Dharma

- Esoteric Mystic Hinduism

- Introduction to Hinduism

- Hindu Way of Life

- Essays On Karma

- Hindu Rites and Rituals

- The Origin of The Sanskrit Language

- Symbolism in Hinduism

- Essays on The Upanishads

- Concepts of Hinduism

- Essays on Atman

- Hindu Festivals

- Spiritual Practice

- Right Living

- Yoga of Sorrow

- Happiness

- Mental Health

- Concepts of Buddhism

- General Essays

1. Meditating on No-Self A Dhamma Talk Edited for Bodhi Leaves by Sister Khema)